Report from the “Universal Acceptance: Catalan Online, With All Its Letters” Conference

Experts and activists demand solutions to ensure that Catalan – and all languages – can function fully and equally online

Domain names that can’t be registered. Emails that don’t go through. Forms that crash. Often, they share a common trait: a middle dot, a cedilla, or an open accent — special characters that define the Catalan language but which its speakers are often forced to forgo in order to access the full functionality of the web. These may appear to be technical glitches, but they point to a deeper issue: the ongoing lack of Universal Acceptance, even in 2025.

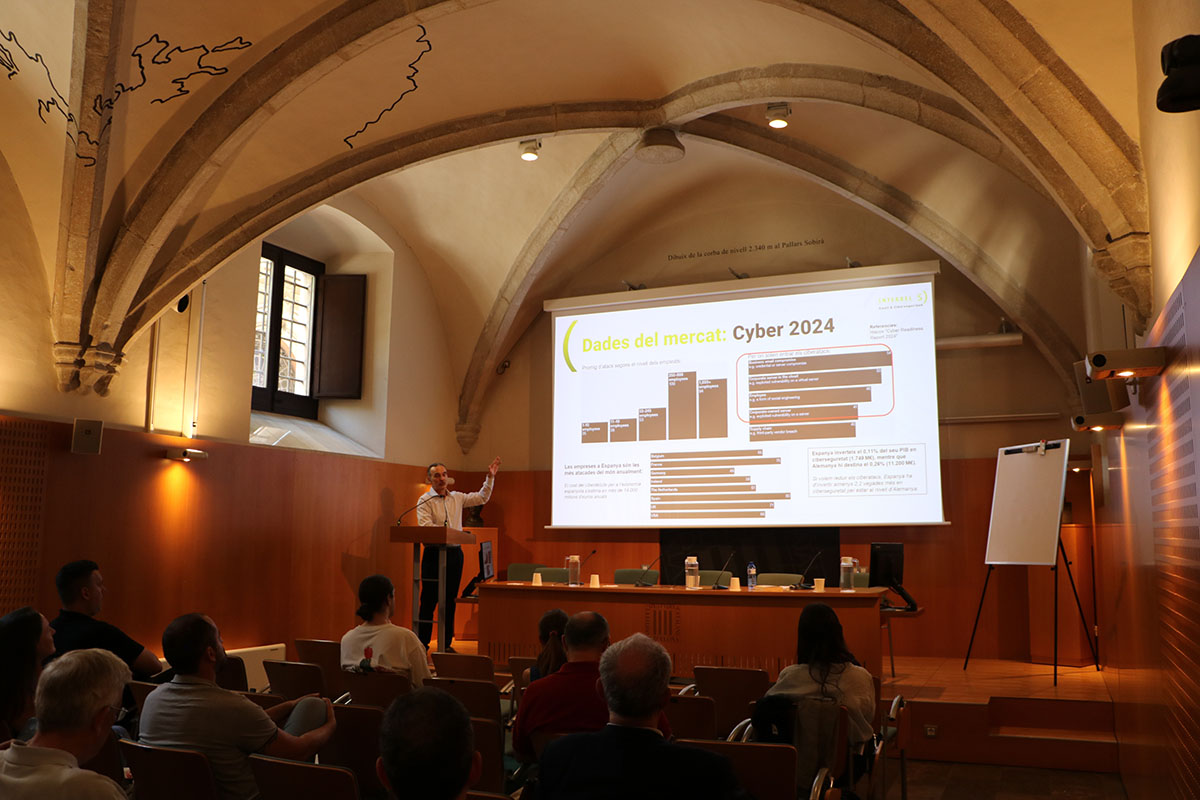

This issue took center stage on June 18 at the Institut d’Estudis Catalans during a conference organized by the .cat domain with the support of the GeoTLD Group and ICANN. Fifty attendees — including technologists, linguists, registrars, and content creators — participated in presentations, roundtables, and talks that blended strategic reflection, technical analysis, and activist calls to action.

20 Years Defending the Use of Catalan Online as an Equal Language

Joan Abellà, director of Accent Obert, opened the session by reflecting on the history of the .cat domain — both a synthesis and origin point for many digital language and cultural rights movements. He recalled the grassroots campaign launched around a simple question: “Why can’t we have our own domain?” Twenty years later, there’s no reason the language shouldn’t also be fully respected in digital communication.

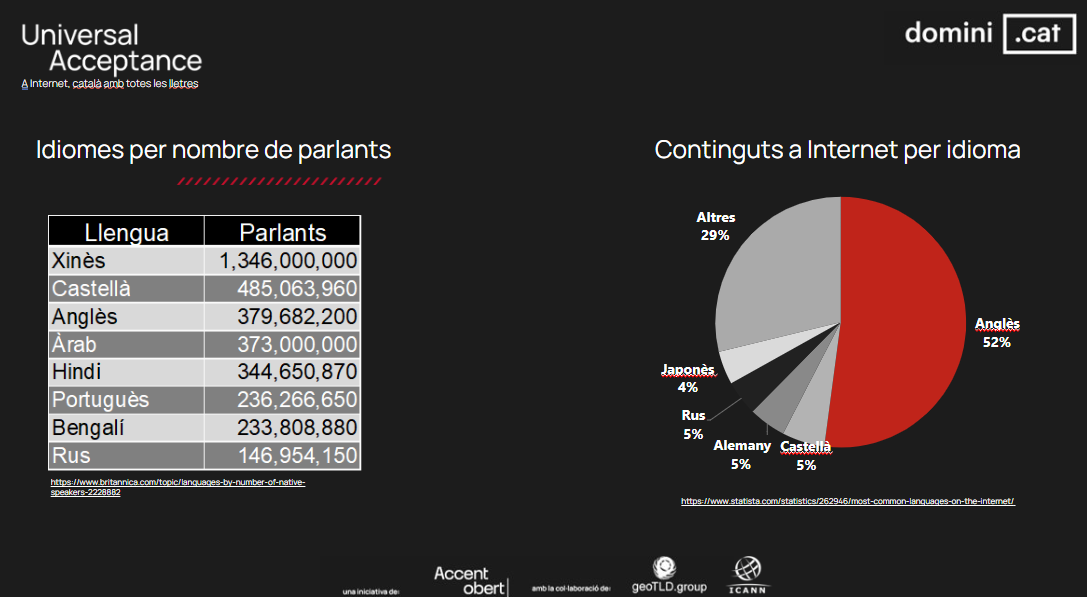

This is neither a minor nor a local issue. Catalan, with special characters in its Latin-based alphabet, is one of many languages affected by the digital dominance of English. Ram Mohan theorized this issue in the early 2000s within ICANN — often described as “the Internet’s governing body”— which led to a strategy to reduce linguistic bias. Since 2010, for instance, it has been possible to register domain names in non-Latin alphabets, known as IDNs (Internationalized Domain Names).

For Nacho Amadoz, president of the GeoTLD Group, achieving Universal Acceptance is essential for a truly multilingual Internet: “It’s a matter of user rights,” he stated emphatically. Acknowledging the slow progress, he outlined the key areas of ongoing work: technical training, awareness campaigns, policymaking, and stakeholder engagement.

Bea Guzmán, head of the .cat domain,, illustrated the linguistic diversity online with data — a picture that still does not reflect global language diversity. But the situation is slowly improving thanks to initiatives like the .cat domain, which in 2006 pioneered giving cultures their own space online — a trend set to grow exponentially with the next round of domain creation in 2026.

This trend represents both a success and a temporary obstacle to interoperability, challenging the principles of Universal Acceptance. Guzmán highlighted how low user awareness leads people to unknowingly give up their digital rights in exchange for a smoother tech experience. Even in a domain like .cat, which supports special Catalan characters, only 1.1% of over 113,000 registered domains use them.

When a Domain Isn’t Enough and Compatibility Becomes a Privilege

In a public-facing demo, Pep Masoliver and Roman Roset, from Accent Obert’s technology department, showed how special characters can cause common online functions — forms, emails, and services — to fail. “If you can’t create an Amazon account with a domain that includes a dieresis or a middle dot, there’s no point in registering it,” they said, revealing how the problem affects everyday users.

This view was shared unanimously by major registrars at the conference (SW Hosting, CDmon, INWX, Nominalia). While all support IDNs, they can’t guarantee full functionality because a handful of tech giants control the infrastructure needed for most services to work online.

The registrars called on absent but key players — software and hardware providers — to align with the Universal Acceptance agenda and calculate the cost of updating digital systems to ensure full language compatibility. But for now, the private sector has few incentives. Registrars like Nominalia report only around three IDN-related requests per year.

A Call for Digital Language Sovereignty

The event also gave space to activism. Linguist Valentina Planas — known online as “La Incorrecta”— made a forceful appeal for digital sovereignty: Being Catalan is exhausting, but we must not give up. It’s our right to use our language, including online.” Using her signature ironic tone, she shared a personal tech anecdote involving a kitchen robot, lamenting how “we shouldn’t normalize writing incorrectly just to be understood by machines.”

A sentiment echoed by Gerard Soler from Plataforma per la Llengua, who noted frequent complaints about the inability to use, for example, the “ç” in Bizum. Thanks to advocacy work, the app has had a full Catalan version since 2022. Gradually, the banks using Bizum are also starting to accept Catalan special characters in payment fields.

In a roundtable led by journalist Albert Cuesta, speakers Núria Ribas (Amical Wikimedia), Marc Antoni Malagarriga (Working Group on the Middle Dot), and Vicent Ferrer (Acció Cultural del País Valencià) demonstrated how Catalan speakers are actively defending their linguistic identity in the digital sphere.

As Planas concluded: “Catalan only has a future if it also has a future online — in systems, domains, and every digital interface. With dignity.”

A More Diverse Internet Requires Greater Digital Literacy

Roman Martín of ASCICAT closed the day by warning that lack of Universal Acceptance can open the door to digital fraud and phishing — criminals exploit character confusion for malicious purposes. The solution? Better use of available tools, more digital culture, and more training.

Toward a Fairer, More Diverse and Interoperable Internet

That — generating and sharing knowledge — was the goal of this first Universal Acceptance conference. A lineup of expert speakers showed that linguistic compatibility online is not a technical issue, but a design flaw in the digital world that must be corrected to uphold user rights.

As Nacho Amadoz put it: “If the Internet wants to be truly universal, it must include all languages, all identities, all characters. And all accents. Without exception.”